Happy Thanksgiving – Feliz día de acción de gracias

This Thanksgiving, we would like to thank all of our TaJu Educational Solutions friends, extended family and partners around the world. Happy Thanksgiving! Be well my friends!

English Only Here: The Impact of Restrictive Language Policies on Language Identity and Student Achievement

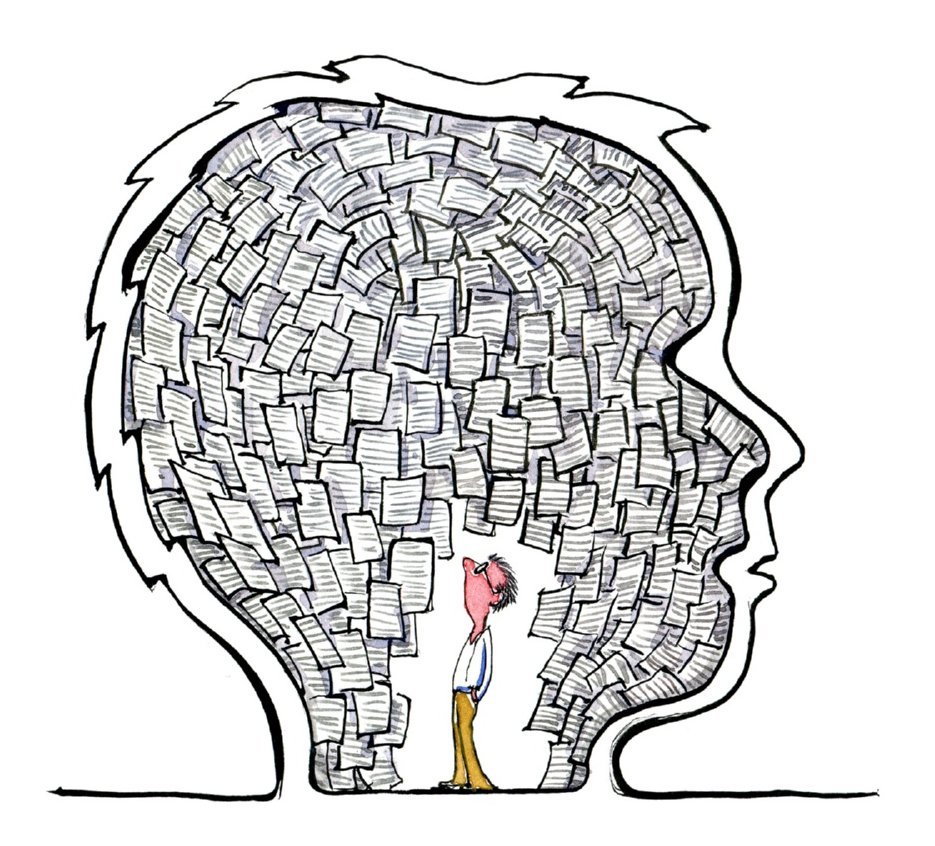

Last week, I had the opportunity to be part of a critical dialogue about the past, present, and future trends in the education of linguistically and culturally diverse students (also called bilingual, emergent bilingual, EL’s, and ELLs) with Manuel and Dr. Kathy Escamilla. It was a dialogue that created so many flashbacks of my experiences as a student. It was also a humbling reminder of my last two decades as an educator. The lingering message was a narrative of language policies that coerced linguistically diverse students out of their first language. And schools issuing a growing number of punishments for “failing” to acquire a second language almost instantaneously. The sad reality is that in many ways it was a terrible walk down memory lane that I almost did not want to take – and yet, I’m infinitely grateful that I did. The day left me hungry to change the reality of this narrative for current and future children who depend on schools to prepare them for a future of their choosing. The message of the day was powerful, but one question in particular keeps calling my attention. What are the implications of losing a language? It seems like a simple question? And yet it is incredibly profound. Many of us serve language learners in various program models with strong and (at times) immensely restrictive language policies: Don’t speak your native language in class. You need to find other friends so that you can practice English during recess Put a quarter in the jar if you use your native language These are practices and messages I have heard in schools across the country. But why are these policies problematic? Why should all educators be concerned with the consequences of restricting a native language in school? Personally, I know that my language is part of who I am; it is an essential connection to my past, my culture, my funds of knowledge. My language is how I interact with, negotiate with, and socialize with this world. My language is a point of pride that honors my culture and concurrently is refined and expanded by that same cultural connection. My language is my window to learning and gateway to new ideas embedded in books. To take away my language is to take away my right and access to interact socially and academically… to devalue the legitimacy of my identity… to render me powerless. This is the reality faced by the fastest growing student group in schools across the country, language learners. Valuing bilingualism as an asset, not a deficit, is a critical mindset needed. Even still, participation in learning may be a great source of struggle for language learners depending on their skills in English. Every successful interaction in English helps students to renegotiate their academic, social, and individual identities in more powerful ways – ways that will lead to greater academic success. Every miscommunication, idea, and thought that is stifled by the limited words and grammar they are able to produce causes a renegotiation towards greater inequality – one that will translate into greater achievement gaps. Educators must consider how to maximize students’ opportunities to fully participate in the learning community while also learning the rules, structures, and vocabulary of English. The best place to start is to use language policies and practices that provide language learners with a more powerful position to access social networks, opportunities to speak, and the tools to engage in cognitively challenging work. So how do educators do this? Include texts that reflect the interests and background knowledge of students. Utilize bilingual word walls to allow students to connect academic vocabulary with words in their native language. Engaging students in strategic learning around metalinguistic awareness (the ability to see, analyze, and manipulate language) helps to develop greater proficiency in English. Increase the amount of student talk that requires complex thinking. In doing so, students will have greater opportunities to master content knowledge by utilizing academic language, which are inter-related processes regardless of what language is used.

A Dedication to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr

Today is a day dedicated to honoring the legacy and impact of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. And while many simply enjoy the extra day at home, it is vital to reflect on what this day truly means. His life’s legacy is one of equity, access, equality and the ability of each person to realize their own dreams regardless of race, color, or creed. As an educator, I see the overwhelming challenges our children face to realize that legacy every day. Not all students experience an equitous educational experience, have access to the conditions that will ensure their success, or are faced with a set of experiences that prepare them to realize their dreams. With barriers existing for so many children (black children, brown children, language learners, exceptional children, children living in poverty, LGBT, and so many other silenced voices), I know that this work can not live on just one day of the year. Rather, we must fight, now more than ever. We must honor his legacy as we serve and guard the amazing children that are entrusted to our care. So let us not be silent, for our children – all our children – are the future and the legacy of our humanity.

Week of June 19th Online PD

These two online workshops are “game changers” for schools that are ready to focus on accelerating ELLs language development and ability to tackle the CCSS!

How Is Everyone a Language Teacher?

Over recent years, it seems that the challenges students face when having academic conversations have only gotten larger. Students struggle to have meaningful conversations, they struggle to stay on topic, they struggle to find the words to help them speak knowledgeably and precisely about the topic being discussed. While these challenges exist for a number of reasons, the reality is that these are challenges that impact us all. Whether we are teachers of Reading, Math, Science, junior high, high school, or the elementary level, we all rely on language as the vehicle for learning and measuring the impact of our teaching. And in the world of education, oral language is king. We talk, explain, lecture, discuss, read out loud, and listen each and every day. Oral language is part of the fabric of teaching. Yet, do we actually know what oral language actually is? Well, oral language is generally made up of the following five elements: academic vocabulary – understanding the meaning of words (T1 – T 3) morphological skills – understanding the impact of word parts on word meanings (including prefixes and suffixes) syntax – understanding the rules of word order and grammar phonological skills – understanding the range of sounds pragmatics – understanding the social rules and nuances of conversation and communication Instruction that works to develop students’ oral language has to begin with the recognition that students can not be sheltered and kept from critical questions with no easy answers. Rather, as teachers we have a great opportunity to layer in oral language in order for our students to access this rigorous content. While we will talk more about the strategies that increase oral language development, the following are just a few ways that you can begin to do this: Make time for focused and critical discussions, Promote meaningful and deep conversations by providing language frames to guide the communication, Explicitly teach students the rules of how to have conversations prior to using structures like turn and talk, Provide opportunities for students to engage with rich and complex texts, Advance students’ academic vocabularies by selecting fewer words to master more deeply with a focus on application in all areas of their language use, Allow time for reading aloud to students in order to provide access to more challenging texts thy may not able to access on their own Use content area texts to teach critical grammatical structures that Allow time for students to talk through their understanding before putting anything to paper.

VOCABULARY JOURNAL: Building Academic Vocabulary with SPEED™

It’s finally available!!!! The student journals for academic vocabulary called, VOCABULARY JOURNAL: Building Academic Vocabulary with SPEED™ is now available on Amazon! So why did we create this resource? Well, we know that challenges with vocabulary strongly influence the readability of a text (Chall & Dale, 1995). Not only that, but lacking vocabulary is known to be a critical factor in overall school failure or success in disadvantaged students (Biemiller, 1999). Yes, it is a disheartening fact that ELs and struggling students have notably lower vocabularies than their counterparts ((Oller & Eilers, 2002), because these vocabularies are such strong predictors of overall achievement. One reason for this is that their native English learnering peers acquire an estimated 3,000 new words each year in school (Nagy & Anderson, 1984). This vast number of words helps native English students achieve growth in reading comprehension and their ability to communicate mastery across content areas. The self-fulfilling prophecy is that this reading growth and content mastery creates the path for native speakers and students to, in turn, learn more words which will fuel even further growth down the line. But for EL’s and struggling students, the challenge with vocabulary is greater than just acquiring the same 3,000 new words each year. These students come with such a range of size in their vocabulary (Snow & Kim, 2007), that it is almost impossible to calculate what it would take for these students to reach the same vocabularies, and by extension the same opportunity for school success, as their native classmates. It is because of this that it becomes almost impossible to have a singular approach to helping them catch up to their peers. So what is the solution? Well, the solution needed to be one that blossomed from the uniqueness of each learner’s situations and the reality of the schools in which they learn. The solution to this challenge came organically, from studying tons of research, watching great teachers, and analyzing the impact of different approaches on student learning and engagement. I call it SPEED™. SPEED™ is a comprehensive vocabulary acquisition process that allows for the introduction, building background knowledge, explicit teaching, meaningful and varied practice, and metacognitive dialogue that allows EL’s and struggling students to acquire vocabulary words quickly and profoundly. Since many studies suggest that the amount of instructional time devoted to building vocabulary is simply not enough, part of the SPEED™ approach includes teachers’ willingness to commit to increase the amount of consideration given to vocabulary instruction. Again, the commitment is to consider vocabulary needs when planning, not to necessarily increase the amount of time. In parts 1 and 2 of this book, we will share simple and time-efficient ways of doing this. An additional piece that makes SPEED™ effective is that students are asked to develop goals around their word usage outside of vocabulary “time”. This goal setting, helps students transfer the knowledge of the vocabulary gained during safe practice into other situations and times when the term would be appropriate. So, are you ready to help your students acquire academic vocabulary with SPEED?

1 Research-based Strategy Truly Great Teachers Use

In the world of high stakes testing, we often worry about how we are going to “cover” all the standards in our curriculum, especially when we serve EL’s (English Learners) and struggling students that need greater amounts of support. It is a real concern with no easy answers. So what is one part of the solution? Chunking. Chunking is an approach based on cognitive theories, or constructivism. It is based on how teachers “chunk” or group information into logical and related units. These units are then easier to commit to memory because it reduces the amount of cognitive stress levels as the amount of information that the learner has to process is divided into smaller, more manageable units. Teachers’ ability to effectively chunk information for learners aides in and facilitates much needed information retrieval so that students are more easily able to engage in higher order cognitive demands. One of the most powerful benefits of chunking for EL’s and struggling students is the fact that since teachers are planning smaller chunks of information as a unit, it allows each element within that unit to serve as background knowledge for the next piece in the chunk. Teaching, then, simultaneously becomes new information and background knowledge for students to make vital connections to the information already present in their long-term memory. So, for example, if I want to teach student how to compare themes in literature, I know that students must be able to do several things. They must learn how to make comparisons, make inferences, understand what a theme is, cite evidence from a text, etc. Each of these units could be sequenced as chunks that go deep into new learning before moving into the next chunk. So when thinking about what to teach next in your unit, try not to think about what fun holidays or activities might be around the corner. Try to ask yourself, what’s the next chunk of learning that will make a difference for students’ ability to master the standards? Here are five great reasons that you should chunk. Creating small pockets of learning for students to hang on to promotes greater learning outcomes Sequenced “chunks” build background knowledge for the next “chunk” Chunking supports short memory functioning Allows for closure of each small “chunks” which enhances recall Facilitates comprehension

5 Reasons Why Expectations Change Results for all Students, especially ELLs

It seems simple, that as educators, we have the same high learning expectations for all students in given classroom, grade level, or school. After all, we wouldn’t want to knowingly deny the access and benefits of a high-quality educations to any child. And the reality is that the vast majority of educators do not approach their educational planning and instruction with low expectations in mind. After all, this ideal of high expectations is founded on the concept that whether you think you can or you think you can’t, you are probably right. Our beliefs and expectations have a profound impact on our hopes for accomplishment and effort to succeed. So what does this mean? It means that students who are expected to learn at high levels tend to do so, while students who are expected to learn at low levels also tend to achieve exactly that – regardless of their ability. This phenomenon has long-been researched and is most commonly known as the Pygmalion Effect. In this study of the self-fulfilling prophecy, people internalized their positive and negative labels. Their level of success followed their labels accordingly. The conclusion was that by increasing the leader’s expectation of those who followed, the performance will result in better performance by those who were following them. The impact of this study has implications in more than just education and extends from education, to social class, and of course, ethics. Yet, when we are faced with students that don’t speak English, that read significantly below grade level, and are otherwise challenged to perform at grade level expectations, many are at a loss in terms of what to do to marry the competing worlds of meeting students’ needs and meeting the Common Core State Standards. And whether intentionally or unintentionally, we find ourselves lowering the expectations for these groups who already have a history of underperforming. And while the challenge is certainly a perplexing one, this solution only results in further exacerbation of the very problem. So what is a reasonable, yet high expectation for our struggling students, particularly those who are English Learners? And why should we commit to this course? Research shows that shifting our instruction to support the development and emphasis of more academic English leads to greater academic success. Without intervention and increasing success rates for English Learners, they will drop out of high school at twice the rate as the English-speaking peers (Rumberger, 2006). It is true that English Learners achievement levels and growth progress at different rates, but cognitive scientist agree that it is by increasing the success rates on challenging tasks that increasing the rate of growth for all learners. Student access to the core academic curriculum (Callahan & Gandara, 2004) – which is now the Common Core State Standards – is one of the most important variables leading to English Learners growth and ultimate success. Research has shown that the simple act of asking students (particularly English Learners and struggling students) to elaborate one powerful way to challenge students in a manner that demands that they explain the details of what they know. This is an opportunity to solidify connections in their minds which is proven to have a greater impact on rate of growth and overall achievement.

Essential Language for Reaching the Common Core:

Over the last few weeks, we have talked at length about a number of ways to increase your students’ vocabulary so that they are able to access increasingly more complex text and grow as readers and intellectual beings. In fact, with the arrival of the Common Core State Standards, we’ve all become more mindful of the complexity of texts we present to our students and the tasks they are given to process what they’ve read with increasing depth and challenge. In order to begin accessing increasingly complex texts, we know that one thing students need to acquire is a growing bank of words at their disposal in order to make meaning. However, in order for students to begin to successfully tackle more rigorous tasks, there is another critical need. It is absolutely vital that students understand what a performance task, practice application, or assessment is asking for them to do with the same level of fluency and automaticity that we expect from them when reading any text or passage. The Common Core State Standards offer us two categories of words that students must master – nouns and verbs. The nouns of the standards detail the key concepts and ideas that are essential take aways in Literacy, Math, and NGSS. Without access to these words, students will struggle to make meaning of and from the standards with rigor or precision. The verbs of the standards outline the thinking and mental tasks for which students must be prepared to engage. It is one thing to give students the opportunity to critique a peer’s argument, and to revise their argument based on that feedback (depth of knowledge 4). It is another reality for that student to expertly know what it means to offer a peer that critique. There are a number of strategies that you can leverage in order to teach these words such as: gradual release with modeling, visual representations, total physical response, four square, concept mapping, categorizing, creating student glossaries/dictionaries, gradients, word play, and more. Additionally, it is critical to know what these high leverage words are. While the nouns vary between the different subject areas and grades, the following list of verbs will be an incredibly helpful starting point in teaching your students words that will help them to think with the depth necessary to successfully complete tasks and master the standards. Analyze Articulate Cite Compare Comprehend Contrast Delineate Demonstrate Describe Determine Develop Distinguish Draw Evaluate Explain Identify Infer Integrate Interpret Locate Organize Paraphrase Refer Retell Suggest Summarize Support Synthesize Trace If there are additional ways that you help your students to access the language of the Common Core State Standards, please comment below. Or you can email us at tajulearning@gmail.com.

Part 5: Teaching Cognates to English Learner Students

When it comes to English Language Learners, it is critical that students have the opportunity to see their native language as an asset. Particularly for native Spanish speakers, a way to do that is to help them understand the sheer amount of academic vocabulary they have at their disposal through the use of cognates. Teaching students to leverage their native language to their advantage by looking for cognates is incredibly powerful due to a number of factors. One of those factors is the nature of these cognates themselves. Many of the cognates in Spanish seem to be high use words that cross domains (Reading, Science, Math, etc.). For example, matemáticas and mathematics are cognates in Spanish. The fact that these are “high utility” words only strengthens the power of instruction with them because of the the impact of multiple exposure to a specific set of words and student acquisition of the “layers” of meaning a given word might have. One strategy to do this is to following the process below: Teach students what cognates are – “words that mean just about the same thing in English as in your native language”. Have students look at for words that might be cognates in authentic texts Have the students answer the following questions about the word What is the English word and what is the native language equivalent? Does the word mean about the same thing in both languages? Do the words sound alike? Do the words look alike? Are the two words cognates? Why or why not? Are there any parts of the word that are not the same? While this strategy above is not fool-proof, it does begin to help students see how to pull from their native language knowledge in order to have access to a larger bank of words, concepts, and background knowledge which can only help. If you have questions about cognate instruction, please don’t hesitate to leave your question below. Additionally, if there is an additional topic that you would like to see posted or additional ways that you engage your students to invest in word learning, please comment below. Or you can email us at tajulearning@gmail.com.